Die erste „Artist of Sharing“ ist die Australierin Tarsh Bates.

Tarsh Bates arbeitet an der Schnittstelle von Kunst und Wissenschaft. Als Doktorandin im Labor für künstlerische Produktion, SymbioticA, School of Anatomy, Physiology & Human Biology der Univertsity of Western Australia, setzt sie sich umgehend mit Candida albicans, einem Hefepilz, auseinander. In Berlin sind ihre Arbeiten bis zum 30. April 2016 bei Art Laboratory im Rahmen der Gruppenausstellung „The Other Selves. On the Phenomenon of the Microbiome“ zu sehen.

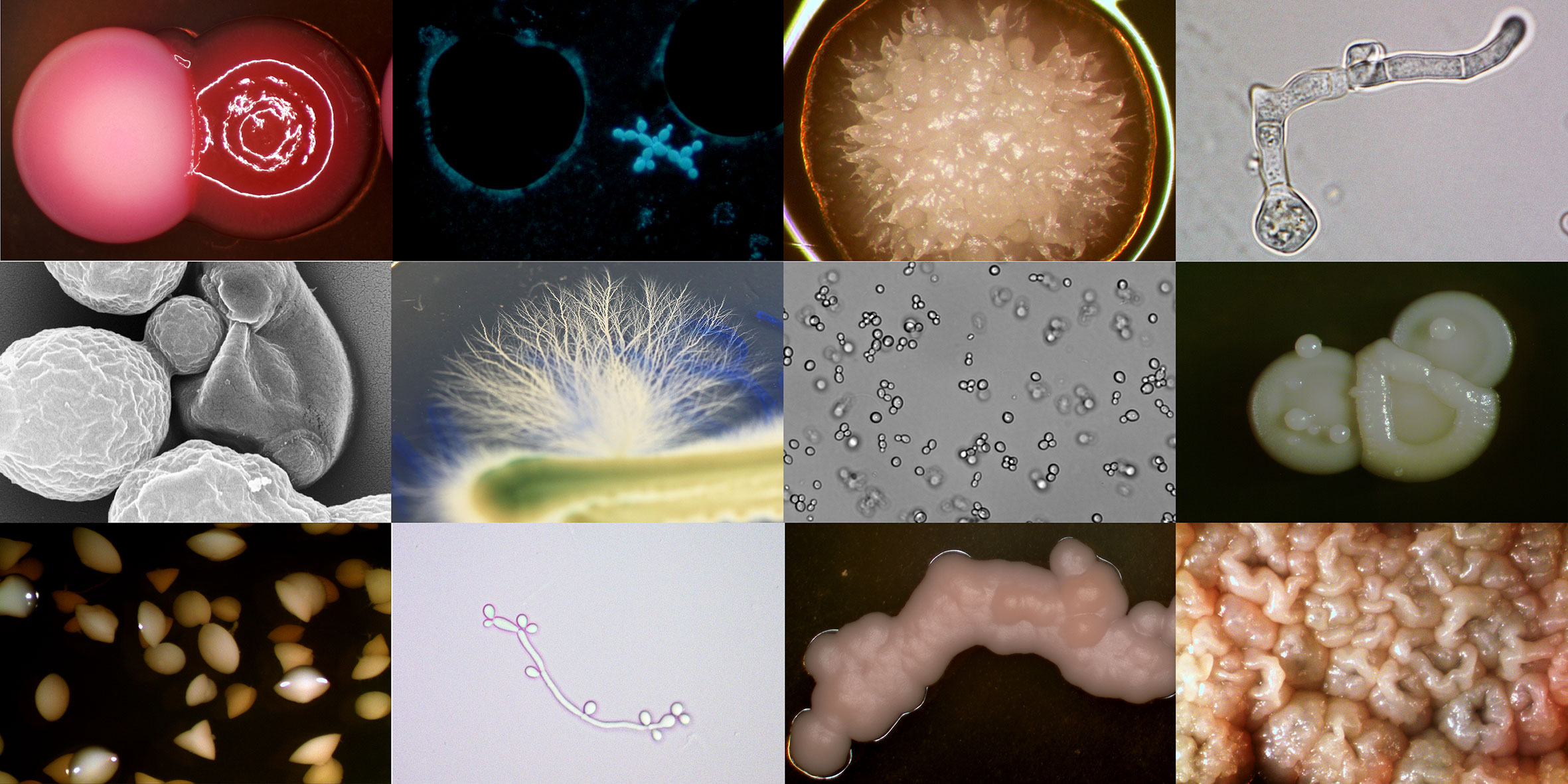

Ins Viktorianische Zeitalter etwa entführt Bates den Besucher mit ihrer Arbeit „Surface dynamics of adhesion“. Hinter einem bordeauxroten Sofa befindet sich ein farblich harmonierender Plexiglasrahmen. Doch der Inhalt, der in seiner Struktur an beflockte Tapeten aus dem 19. Jahrhundert erinnert, setzt sich aus Blut der Künstlerin zusammen, dem sie Candida albicans hinzufügte. Eine weitere Arbeit, deren Titel sich auf die Terminologie Martin Heideggers bezieht, „Ereignis, Gelassenheit und Lichtung: A love story“, zeigt im Zeitraffer-Modus Candida albicans, das sich mit einem von der Künstlerin stammenden Serum vermischt. Es ist vor allem eine Frage, die Bates umtreibt: „Was bedeutet es, Mensch zu sein, wenn unser Körper mit mehr als einer Billion Zellen ausgestattet ist, von denen doch nur die Hälfte menschlicher Natur ist?“ Und wenn eine Zelle sich in zwei identische Hälften teilt, die getrennt weiter existieren, wie bemessen wir dann unsere Lebensspanne? Ist es die Zeit der intrazelluaren Kommunikation in uns? Ist es die Dauer von Reproduktion und Replikation auf zellulärer Ebene? Wenn sich dort ein Teil von uns ständig wiederholt, wann sterben wir? Erst wenn auch die letzte der Zellen, aus denen sich unser einst lebender Körper konstituierte, aufgehört hat, sich zu teilen und zu vermehren? …

The Unsettling Eros of Contact Zones, and other stories: hosting Candida albicans

Tarsh Bates, SymbioticA, The University of Western Australia

Candida albicans is a yeast; one species of the hundreds that live in the ecosystems of the human body. It dwells in the multispecies communities within our bodies, on our dark, moist, warm folds, consuming sugars and other nutrients. Environmental change invites the usually companionable yeast to occupy the desolated spaces vacated by bacterial inhabitants destroyed by antibiotics or excessive use of antibacterial or antiseptic cleaning products. Immune inhibition incites yeast cells to morph into hyphal cells that put down roots into human cells and tissue. Inflamed tissues riot, trying to evict the intruders. The host absorbs anti-fungals, yoghurt, garlic; purges sugar, carbohydrates, fruit, to soothe the populace.

We have co-evolved; human bodies are the ecological niche of C. albicans. As a commensal of mucosal surfaces and the gastrointestinal tract, it benefits from us without damaging us. The complexity of the human immune system still evades us and the host-disease relationship between Candida and Homo is contentious and uncertain. Does the human immune system consider C. albicans “the commensal” to be “self”? Does C. albicans trick us into ignoring it, or is a ravaging beast kept at bay by a robust immune system and other microorganisms, as suggested by the majority of experimental research papers? Recent studies have shown that commensal C. albicans cells produce different proteins than cells that actively cause disease, suggesting a more active C. albicans than is usually allowed for. After all, engaging with a host’s immune system is highly resource intensive for both parties, and why not just hang out if you can?

“this fungus is inside all of us and it’s never about eliminating it. You have to kind of just live with it.” — Björk (2011) Virus

Candida are internal, microscopic, invisible, simultaneously short lived (days) and immortal. Can we comprehend how candida might perceive time? Is it the time of intracellular communications between host and self or the temporality of reproduction and replication – when one cell becomes two, identical, yet separate? If self is constantly replicated, when is one born? Does one die? How is a life measured? Is candida time the temporality of consumption, when food appears and reappears? Does it recognise periodicity as intervals of infection; an exuberant fecundity, or as length of mycelial growth?

Ereignis, Gelassenheit und Lichtung: A love story (2015)

Until recently, laboratory studies of Candida were performed by extracting a sample of the fungus from a host and growing it using a standard microbiological technique: on the surface of a solidified agar nutrient medium in a petri dish incubated at human body temperature in a steel box (an incubator). Typical single-celled microbial colonies appear during the three-day incubation period after which the nutrient supply is exhausted and a new plate is cultured. Candida on agar are benign and asexual, replicating through budding – not dissimilar to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the yeast species used in bread or beer making. Within a host body, however, Candida are omnisexual and polymorphic, able to switch between asexual and sexual reproductive strategies and several morphological states. Switching is the result of a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, including temperature, pH, food supply and moisture. Candida morph between various states: yeast and hyphal cells; an opaque form necessary for sexual mating; pseudo–‐hyphal cells; and chlamydospores. All are distinct cell types involved in different modes of pathogenicity and virulence. Can the (apparently) sexually dimorphic coagulation that is the human body understand this extravagant fecundity?

Following scientific care instructions, I subculture the Candida every three to four days in a biosafety cabinet in a PC2 laboratory to ensure a ready supply of nutrients. I am very conscious of my embodied relationship with this seemingly benign organism and grow fond of the smooth, shiny, creaminess of the colonies. In the ritualised environment of the PC2 laboratory, with my lab coat, gloves and sterilising ethanol I become highly aware of my actions when caring for this critter: flaming the inoculation loop to sterilise it; stroking the agar plate to remove a colony; streaking the colony onto a new plate in the accepted four quadrant streak method; brushing my hair out of my eyes with the back of my gloved hand; pushing my glasses back up my nose; wrapping the streaked plate to prevent contamination; jumping off my chair; opening the incubator; turning the plate upside down to prevent condensation; placing the plates on the incubator shelf; coming in every day to check growth and contamination. I experiment with different media and prepare sheep’s blood agar plates, sampled from the sheep of a local farmer. The blood is red at 55°C and chocolate-coloured at 70°C: the sheep donor is 39°C; I am 37°C.

Many of the foods we consume are produced with or contain a variety of microorganisms, including the basics: cheese, bread, milk, and beer. I mix, knead, bake and offer bread leavened with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans, brie, and hummus to share, inviting consideration of assumptions about microorganisms, our bodies and the food we consume. All microorganisms used to leaven the bread are killed by the baking process, including the candida. The fungus (Penicillium candidum) that envelops the brie is alive. This artwork is both an investigation of the materiality of the organisms and a gentle provocation to pay attention to the organisms that live within us, seep from us, or that we ingest with our food. Yeasts are some of our oldest “messmates,” having helped us to produce bread, beer and wine for millennia. Here, as Donna Haraway says, “companions of all scales and times eat and are eaten at earth’s table together.”

A host is the animal or plant that is the environment for or sustains the life of a parasite or commensal organism. It is a marauding and invading swarm. It is one who provides food and shelter, and the sacramental bread of the Eucharist. Hosting entails a response-ability to the stranger. We are the environment for and sustain the lives of the commensal C. albicans, and the parasite C. albicans is a marauding swarm (although from the perspective of a C. albicans cell, our immune system is the marauding swarm); we provide food and shelter, and bread leavened with C. albicans is broken and shared to know and feel more, about how to eat well—together. In French, a host is simultaneously “host” and “guest”— is C. albicans host or guest? Which are we?

N.B. Aspects of these musings are borrowed from Bates, T. (2013). “HumanThrush Entanglements: Homo sapiens as a multispecies ecology.” Philosophy Activism Nature, 10, 36-45. and Bates, T. (2015). “We have never been Homo sapiens: CandidaHomo naturecultures.” Platform: Journal of Media and Communication, 6(2), 16-32.

More Information about Tarsh Bates