During the numerous civil disobedience movements of the 1960s, the American Civil Rights Movement, the anti-Vietnam War movement, the Women’s Liberation Movement, the painter Louise Fishman demonstrated for the rights of women and homosexuals. The current generations of women, lesbian and female artists owe her a lot. Today Louise Fishman is bewildered concerning the backlash in politics and society under “dt” how she names the president in small letters. YEAST-art-of-sharing met with her in Venice, where she spent a two months residency together with her spouse Ingrid Nyeboe via the Emily Harvey Foundation.

What was it like to be a female artist in NYC in the 1960s–1970s?

In the early sixties, I was living and studying art in Philadelphia. I traveled to New York as often as I could to see art and to get a glimpse of the New York art world. I had expected to be able to meet the Abstract Expressionists, and join a community of artists. I learned otherwise, when I visited the Cedar Bar on University Place in the Village. It was famous as an artists’ hangout. My friends and I were sitting in a booth towards the back when I noticed a booth full of famous artists closer to the front of the restaurant. Milton Resnick motioned to me to come his booth. I was very excited – along with Resnick sat Joan Mitchell and I believe, Franz Kline.

I walked up to his booth only to discover he wanted me to sit on his lap. At that moment I understood the sad truth—I would always be an outsider to that community. I am a lesbian, so unlike many women artists of that time, being a sexual partner would not be a possibility and neither a path to that community.

Did you join any feminist activist groups? Who were the female artists around you?

When I returned to live in New York in 1965, I had no artists’ community whatsoever. I worked as a proofreader and editor, painting at night and on the weekends. In the late sixties, I became involved with the women’s and lesbian movement, first, as a member of Redstockings and Upper Westside Witch, and then as a participant and activist of lesbian/queer radicalism.

My painting life was separate from my political life, as there were no other artists in the movement that I knew about. In 1969 I helped form a women artists’ consciousness raising group. Initially, I had organized a small CR group, with the sculptor Patsy Norvell, the dancer Trisha Brown, and Carole Gooden, (one of the founders of FOOD Restaurant in Soho—a restaurant founded and run by artists, who took turns cooking.)

My women’s artists group lasted through the summer, and was followed in the fall of that year by another women’s artist group I founded along with Patsy Norvell. Members were Jenny Snider, Sarah Draney, Harmony Hammond, Elizabeth Weatherford, Patsy Norvell and myself. We met weekly for four years, looking at each other’s work and talking about what it meant to be a woman artist. In 1973 we showed our art together at the newly founded Nancy Hoffman Gallery in Soho.

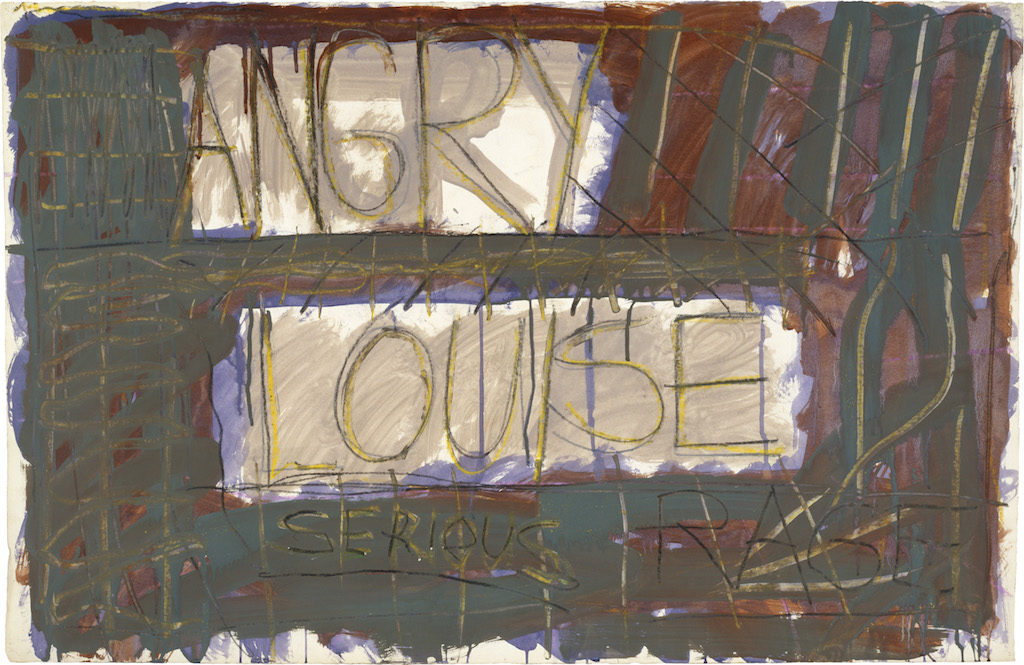

In 1973, Marcia Tucker selected me to be included in the Whitney Biennial. I was thrilled to be included, but suffered severely because of the difficulty of being singled out, separating me from my mother and my aunt (both painters) and the other members of my painters’ group who were not included. That experience, as important as it was for my career, was also a further radicalization. The Angry Women Paintings were a result of that experience.

What do you think of the Guerilla Girls?

They definitely serve(d) an important purpose, and more recently lead to a lesbian art action group—Ridykeulous, which surfaced in 2005. As in Guerrilla Girls, humor plays an important role in their actions, which are feminist and queer. Their political statements are uncompromising and much needed in today’s world, which is so saturated with hatred toward women.

Your mother and aunt were both artists. Has their work been an inspiration for you?

Of course, but in very different ways. My mother, Gertrude Fisher Fishman studied with my aunt, Razel Kapustin when Razel taught a painting class in the early fifties. The effect of both their politics and their art studies had a big impact on me. They both studied at the Barnes Foundation in Merion.

I had access to my mother’s Barnes publications on Matisse, Cezanne, and Renoir and to The Art in Painting, while I was in high school and art school. Razel’s paintings varied from the influence of her teacher, Siqueiros; there were Russian /Jewish themes via Chagall, Soutine, etc. As a child I was frightened by her paintings, with good reason. But I had enormous respect for her decision not to have children in order to be an artist. Her life was a difficult one—fighting the art establishment who recognized her art, but not without a raw misogymy. She was successful, but suffered intensely – dying while she was only in her fifties.

My mother was more of a colorist, in love with Renoir, Utrillo and Matisse. I was the only one to go to art school. My mother resented me for that, and for my decision to become a painter—as she saw it as competing with her. She painted every day of her life, until physical problems made it too difficult. I was most influenced by their determination and love of painting more than by any particular style.

What about your relationship towards Eva Hesse? You once said, “This is my key to New York” when you saw her work for the first time…

I met Eva Hesse when I worked at the Cooper Union Library of the Decorative Arts. When Eva studied at Cooper Union, she had also worked at the library, under the same librarian, Edith Adams. They were very close, and Eva would drop by from time to time, while I worked there. We had lunch together several times, and when I decided to cut my hair short, she decided to as well. There was some defiance in our decisions. From a mutual friend at the time, Lucy Lippard, I knew she had become very ill. Right after she died, I saw a memorial exhibit of her work at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. It knocked my socks off!

Such a shame we never shared our work with one another. At that moment, I decided I could do anything I wanted to as an artist, use any material I wanted, make sculpture, etc. Limitations were off.

You went back to typical female work such as stitching and quilting. How much was that a comment on the social situation for women?

The Eva Hesse exhibition was in 1970, while I was in the midst of my women’s group and my attempt to discard whatever I could of the male influence of my work. I began to learn stitching, knotting, working with liquid rubber and many other materials I found in the surplus stores on Canal Street in lower Manhattan, where I then lived. I stopped making traditional paintings for several years, returning slowly to painting in 1974/75.

There was a period when you stopped painting. Can you tell us why?

When I was meeting with my women’s group, circa 1969—it quickly became clear to me that all my influences were male! In keeping with the radicality of that moment, I decided to stop painting, and to pursue only what arose independently of the art history in which I was embedded. I cut my large grid paintings into strips and began to weave them together—I searched for any material that could be used to make art—to reflect my new consciousness as a female artist. I made sculptures out of found material—in fundamental ways I tried to reinvent myself as an artist.

In 1973 you integrated language for the he first time. The title was “The Angry Women Paintings”—you painted a series of 30 paintings all with “angry” plus a name of a “female” in their titles. Most were associated with friends but some, like Marilyn Monroe, were added. What do all the she women have in common?

My CR training and my female artists’ groups led me to realize how oppressed we all were. My rage filled the air around me and I understood that I had no choice but to respond to that rage in the only way I could—with the word ANGRY, and with my own name next to it in a painting. The effect was startling and frightening to me: like suddenly taking on what had been an undercurrent theme in my life, something that had never really surfaced. It was under there: a smoldering rage waiting to explode and destroy the world, everything I was, and understood. I made a decision to make an angry painting for my then partner, and then for each of my women friends, and finally for women who had inspired me, that I loved, etc. I wanted them all to stand in front of the painting with their name and the word “ANGRY” to experience the frightful and empowering recognition of anger’s central role in our lives. The suppression of rage was crippling us – separating us from our true power in the world.

We all shared living in oppressive patriarchal societies; as females, then and to this day, we are defined and reduced by standards of inequality, and often totally erased from history!

How did your journey to Auschwitz in 1988 influence your work? What does it mean for you to be Jewish?

I had decided to accompany my friends, Valerie and Frank Furth, two survivors, to give them whatever support I could, since I knew that trip was a great sacrifice for each of them, and I understood how difficult it was for them to return. What I didn’t understand or expect was my own reaction to being there. I was born in 1939 in Philadelphia. My entire early childhood was spent seeing the newsreels, collecting things for the war effort and sleeping through terrifying nightmares. We lived in a veritable Jewish ghetto – I thought everyone was Jewish, except for the Germans, the Japanese and the Italians.

When we arrived at our first stop, Warsaw, I immediately registered the rampant anti-Semitism, despite the fact, that there was just a handful of Jews left in Poland. A Polish woman beggar spoke Yiddish as she plied the visiting Jews, revolting me. A young man we met with retold the story of his mother finally confessing that they were Jews, a fact hidden from him to avoid his own persecution. He was hungry for any information about what it meant to be a Jew. The minute my foot touched Polish soil I was a survivor. The soil was deep with the remains of my people. The grass, the trees nourished with “my Jews.” I remember being so cold that I was trembling during the entire trip.

We visited Prague and Terezin, and then Budapest, meeting the handful of Jews trying to reconstruct their lives there.

When I returned to NY, I was in such a state of rage that I left quickly to avoid getting into fights on the street. My partner and I traveled to our farm in upstate NY, and I returned to my studio there, only to find that I felt there was no point in making paintings again after seeing the decimated landscape in Eastern Europe.

While at Birkenau I had taken a handful of muck, soil, pebbles, and what I assumed included the ashes of my Jews: since the pond (I later realized it was called “The Pond of Living Ashes”) / was the repository for the ashes from the crematorium, which had been emptied by the Nazis, as they tried to cover their deeds when the Allies began to arrive.

With the help and advice from friends, I decided to incorporate that soil into a series of paintings I later called: Remembrance and Renewal, the name of the trip I had been on, sponsored by the Simon Wiesenthal Foundation. The series of paintings were individually titled with the various aspects of Passover, a holiday that had been celebrated even in the camps. Passover is a celebration of freedom.

I am a Jew and will always identify as one. I try to follow the Judaism described by Abraham Heschel: compassion and love for all creatures, despite how difficult I sometimes find that task to be. That is, of course, an utter simplification of Heschel’s teachings. I try to be present when there is suffering.

You talk freely about being a lesbian. Is it still hard to be a woman, a lesbian and a Jew in the art world?

First, from my position as an established artist, I can say that, had I been a man my work would be in many major museums around the world, several monographs would be available, and my auction and retail prices would be more substantial than they now are.

I always felt isolated as a Jew—without realizing that in fact many art galleries and art critics were Jews. I was a bit naïve about the number of wealthy Jewish collectors. It took me many years, conversations and much reading to realize how many of the great art dealers and collectors were (are?) actually Jewish; and also through my reading I’ve learned of their suffering during World War II.

It is far harder for female artists to be represented by important galleries. Female painters, particularly abstract painters, are rarely included in museum shows or art fairs. Just to mention one: Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight, her recent solo show at the Whitney Museum! As an out lesbian, I have fewer connections to the art world. There are many more male homosexual artists, curators and art writers, resulting in somewhat of a bias. That said, I have been lucky to be represented by a gallery dedicated to painting, Cheim & Read. I have been with this gallery for 20 years, since it opened its doors, and I truly appreciate our commitment to each other.

Over the past decades, has the situation for female artists improved?

I doubt it, but don’t really know. There’s a tremendous discrepancy between male and female artists in respect to representation in galleries and museums, particularly in painting. The prices for women’s work are considerably lower than for men’s work—check the auction results.

Right after Donald Trump won the presidential election you went to Venice, Italy, for a two months artist residency. You told me you felt a need to return to New York and join the protest movement.

Venice was a respite, a reprieve for me after the horrid election results; our so-called president continues NOT to disappoint his fascist pals and appointees.

The two months in Venice helped strengthen me for the return to the shadow of our homeland, and to the protests, demonstrations, support of the various agencies that are willing to fight to protect our constitution and our rights as a free people.

How do you feel about the backlash in American society? Isn’t it hard to see that the participatory values you have been fighting for are in danger now?

It is terrifying. And requires renewed commitment to struggle and resistance and, above all for me, to continue making the best art I can.

Are there any plans for a show in Germany?

I certainly hope so, but not scheduled at the moment. The appreciation and understanding of painting is far broader and better informed in Germany than in the USA. I love Berlin, and have always wanted to show my paintings there.

And last but not least: You turned 78 in January, even if that fact is hard to imagine. Are you still “wild at heart”?

Always!